The strategic importance of agribusiness in Brazil’s international relations.

João Campos, the new national president of the PSB party and mayor of Recife, advocated in an interview with Folha de S.Paulo for a political strategy of rapprochement with three specific sectors: evangelicals, informal workers, and agribusiness. “The ideal world is to pull the center closer, not to push it to the right,” declared the politician from Pernambuco.

Comments on evangelicals and informal workers will be analyzed at another time. In this article, we will focus on the mention of agribusiness.

João Campos’ reasoning is valid, and for this strategy to work, it’s important to offer a contribution on how the left can relate to this sector intelligently and constructively.

It would be a shame if sectarian leftism hindered Brazil’s historic chance to crush the far-right and coup plotters, and accelerate its development.

The best way to build this alliance is through information: truly understanding the meaning of agribusiness for the national economy and for Brazilian life itself. The term carries political semantics that often generate prejudice. The word itself, with its suffix “business,” ends up creating an automatic association with purely capitalist aspects, generating resistance that overlooks a fundamental issue: without agriculture, there is no food. The second misconception is to imagine that the sector is composed exclusively of large producers, and the third is to harbor unjustified prejudices against these rural entrepreneurs.

The numbers for soy in Brazil in 2024 reveal the gigantic dimension of this sector in the national economy. The soy production chain generated R$ 650.4 billion, representing 5.5% of Brazil’s entire GDP and directly supporting 2.26 million workers. In exports, soy and its derivatives were responsible for 15.5% of everything Brazil sold abroad. We don’t eat GDP – but we eat soy. It’s in our children’s milk, in the protein that sustains our families, in the food base that allows for the existence of modern urban life.

The oilseed is the protein food base for Brazil, China, the United States, and practically the entire planet. Brazilian agribusiness alone feeds about 800 million people worldwide, with soy being responsible for a significant portion of this food capacity.

It’s fundamental to demystify another prejudice: Brazilian oilseed is not produced by two or three large entrepreneurs. There are more than 236,000 producers spread across the country, with 73% of producing establishments having less than 50 hectares, characterized as small properties. Data from Embrapa reveal that in Paraná, 22% of the total soy production comes from small farmers; in Santa Catarina, 33%; and in Rio Grande do Sul, 20%. Although family farming represents only 9% of the total national soy production (due to the sector’s strong land concentration), its participation is significant in terms of the number of producers and social importance.

Brazil as a Global Soy Power

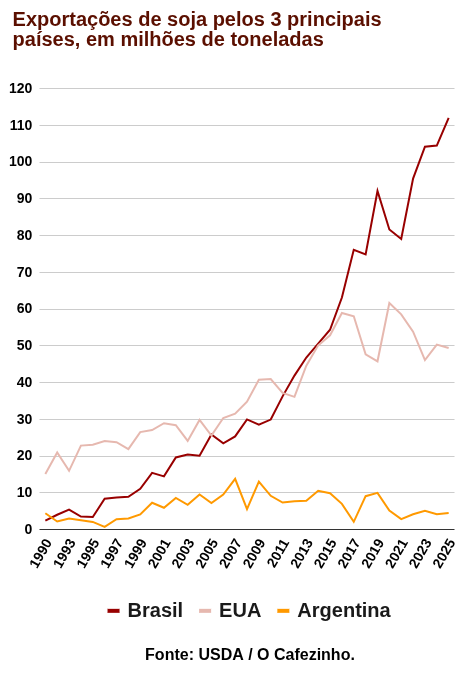

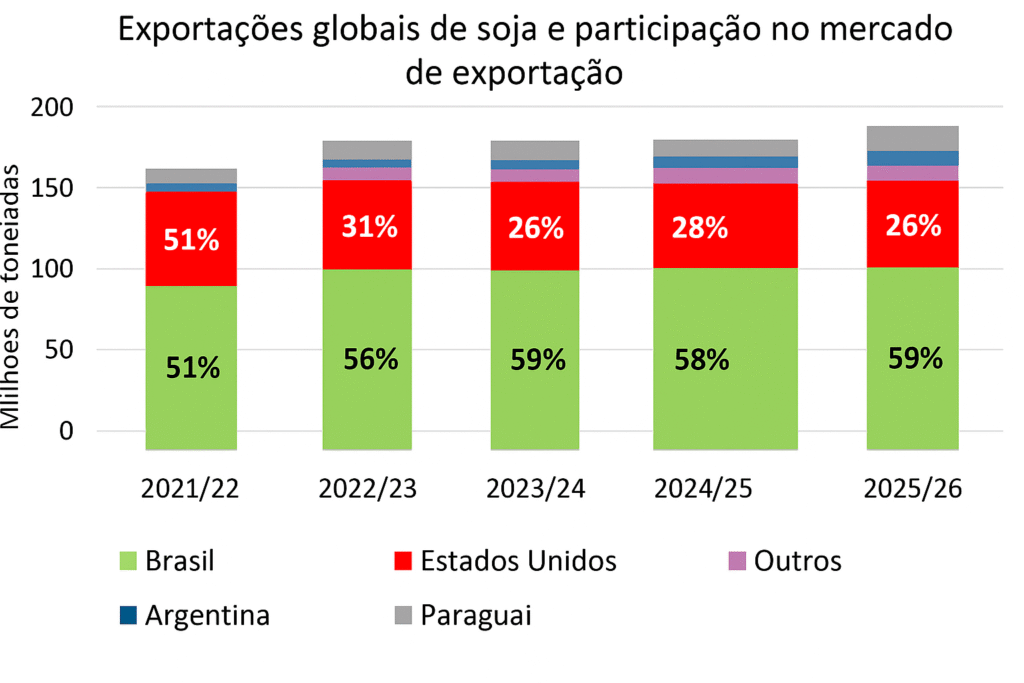

Brazil has achieved a unique position in the global soy scenario, becoming the largest global exporter of the oilseed and surpassing the United States. Between 2015 and 2025 (according to the USDA’s forecast, the U.S. government’s agricultural agency), Brazilian production jumped from 95.7 million tons to 175.0 million tons, a growth of 83%. In the same period, Brazilian exports grew from 54.4 million tons to 112.0 million tons, an increase of 106%. In contrast, the United States, which produced 106.9 million tons in 2015, is expected to reach only 118.1 million tons by 2025 (U.S. government estimate), a growth of only 11%.

This Brazilian revolution has its roots in the scientific work developed by Embrapa starting in the 1970s. Brazil achieved an unprecedented feat in the history of world agriculture: it adapted a plant originally cultivated in temperate regions to the country’s environmental conditions. Soy, traditionally sown between latitudes 35° and 55° north, became viable also in equatorial and subtropical zones, thanks to the efforts of Brazilian researchers.

Brazil developed a unique competitive advantage: while the Northern Hemisphere is in the off-season, Brazil is harvesting, ensuring constant supply to the world market. This seasonal complementarity has transformed the country into the main provider of global food security, especially for China, which imports over 100 million tons of soy annually.

The Perfect Protein: The Secret of Essential Amino Acids

Soy is the only vegetable that contains all nine essential amino acids in adequate proportions for human nutrition. Proteins are composed of 20 different amino acids, 9 of which are considered “essential” because the human body cannot produce them on its own. While most vegetable proteins are considered “incomplete” due to lacking one or more essential amino acids, soy represents a remarkable exception, receiving the maximum score in protein quality. This score places soy protein on the same level as animal proteins considered “complete,” such as meat, eggs, and milk.

National Self-Esteem and Agricultural Technology

Brazil needs to adequately recognize and value its technological achievements. We live in a society that often suffers from an inferiority complex, lamenting not producing cutting-edge cell phones, computers, or automobiles. This distorted view ignores a fundamental truth: Brazil masters agricultural technologies that are as complex as, or even more complex than, the production of numerous industrial products.

Producing 3,500 kilograms of soy per hectare in the Brazilian Cerrado requires mastery of biotechnology, genetics, soil chemistry, climatology, precision engineering, and geographic information systems – an extremely sophisticated body of scientific knowledge.

Modern Brazilian agriculture incorporates technologies at the frontier of world knowledge: autonomous GPS-guided tractors with centimeter precision, drones equipped with multispectral sensors, and variable application systems that automatically adjust the quantity of seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides according to the specific characteristics of each square meter of the field.

Brazil developed and perfected an agricultural technique that revolutionized world agriculture: the no-till farming system. To understand its importance, it’s necessary to know that traditionally, farmers plowed and turned over all the land before planting, completely removing previous vegetation. No-till farming works completely differently: seeds are planted directly over the residues of the previous crop, without disturbing the soil. This permanent “mulch” protects the land from erosion, conserves moisture, improves natural fertility, and drastically reduces fuel and machinery use. This technique, now adopted worldwide, allows Brazil to produce soy more sustainably and efficiently. Crop-livestock-forestry integration (ILPF), a system developed in Brazil and now exported as technology to other countries, represents a sophistication of management that combines knowledge of agronomy, animal husbandry, silviculture, ecology, and rural economics.

The Geopolitical Dimension

Brazil’s position as the world’s largest soy exporter carries geopolitical implications of extraordinary relevance for the nation’s future. With the United States systematically losing market share in the global market and China consolidating itself as the main buyer of Brazilian oilseed, the country finds itself in an unprecedented strategic position in the history of its international trade relations.

This new reality makes it urgent for Brazil’s democratic field to develop a strategic understanding of this sector’s importance for national sovereignty.

Developing a political culture that can better and more strategically understand this sector, especially its geopolitical importance, is essential for the country to maximize the benefits of this privileged position. Brazilian soy is not just an agricultural commodity – it is an instrument of power that can determine alliances, influence trade negotiations, and strengthen Brazil’s position as an emerging power.

The ability to feed hundreds of millions of people around the world gives Brazil a power of influence that transcends traditional trade relations. In a world increasingly concerned with food security, control over the production and distribution of essential proteins represents a form of soft power that the country has not yet fully explored.

Sources:

Embrapa, USDA FAS, Embrapa – História do Agronegócio da Soja no Brasil, AInvest, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Embrapa – Plantio Direto, Embrapa – Integração Lavoura-Pecuária-Floresta (ILPF).