With record production of 4.9 million barrels per day, a trade surplus of USD 25 billion, and the Equatorial Margin on the horizon, the country is consolidating itself among the world’s major oil powers as the global market changes profile.

Miguel do Rosário

Brazil produced an average of 4.897 million barrels of oil equivalent per day in 2025, combining crude oil and natural gas, the highest volume ever recorded in the country’s history, according to Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency (ANP).

Of this total, 3.77 million barrels per day corresponded to crude oil, while the remainder was natural gas converted into oil-equivalent barrels. Ten years ago, total output stood at 3.14 million barrels of oil equivalent per day.

The cumulative increase was 56%.

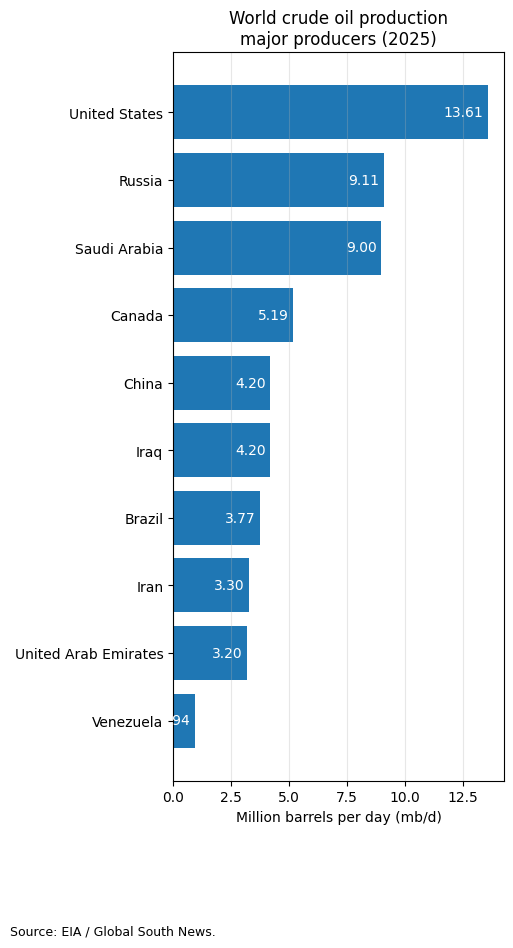

Global crude oil production stood at around 78 million barrels per day in 2025, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). When other liquid fuels are included—such as condensates, biofuels, and natural gas liquids—the total reaches approximately 105 million barrels per day. Brazil accounts for roughly 4.8% of global crude oil production.

The United States is the world’s largest producer, averaging 13.6 million barrels per day of crude oil in 2025, followed by Russia with 9.1 million barrels and Saudi Arabia. China produced around 4.2 million barrels per day in 2024, on a scale close to Brazil’s. Venezuela, despite holding the largest proven reserves on the planet, produced only 940 thousand barrels per day.

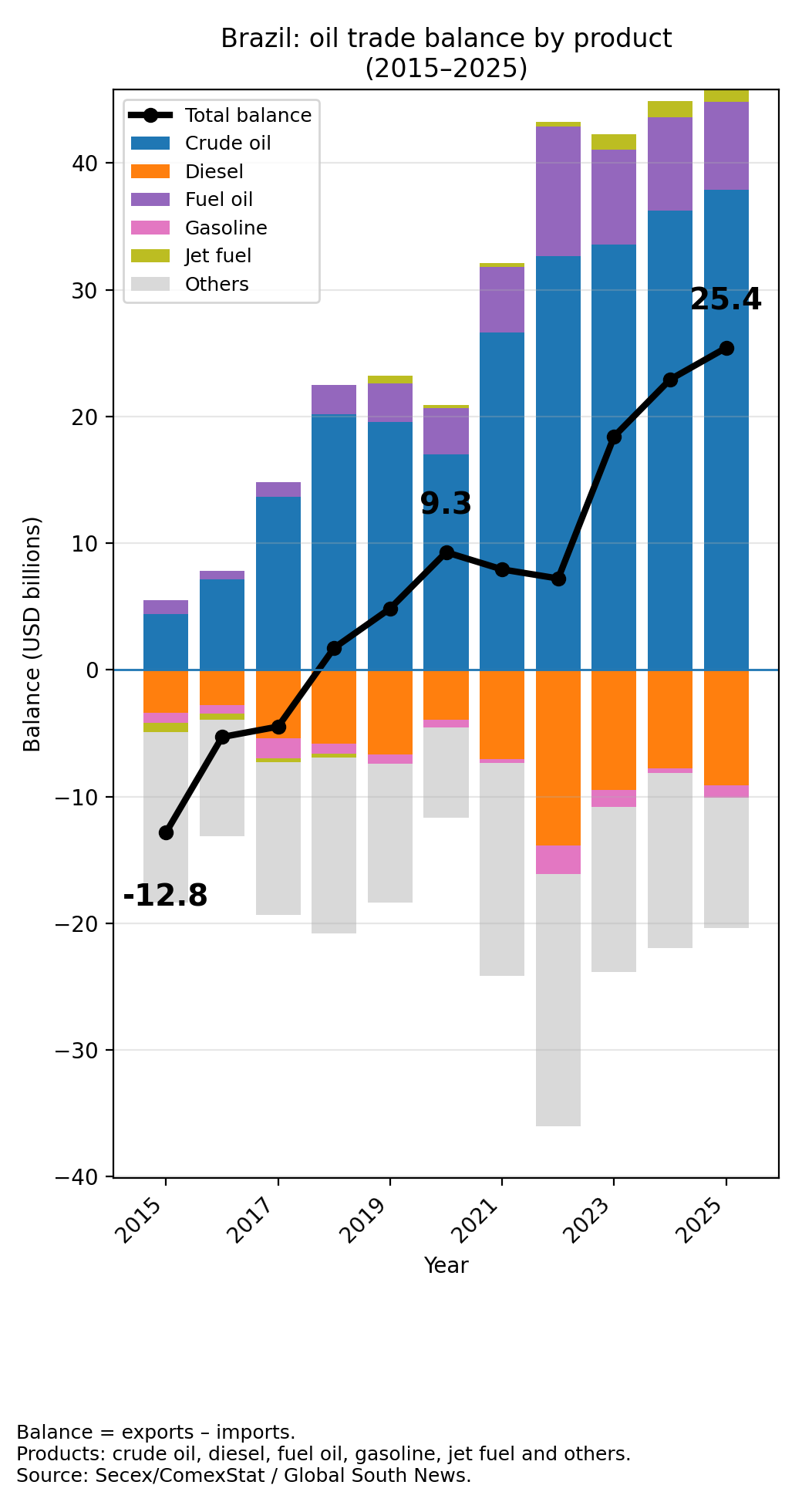

Crude oil was Brazil’s main export product in 2025, generating revenues of USD 44.5 billion and a volume of 98 million tonnes—double the amount exported ten years earlier. China absorbed 45% of this total, consolidating itself as the main buyer of Brazilian crude, followed by India with 8% and the United States with about 7%, whose share fell 26% compared to the previous year after Washington redirected purchases toward Venezuela.

The second-largest export product in Brazil’s oil sector is heavy fuel oil, used mainly as fuel for large ocean-going vessels. Fuel oil exports generated USD 7 billion in 2025, with a volume of 15 million tonnes—more than triple the 4.6 million tonnes exported ten years earlier. Brazil exports this fuel almost without any corresponding imports.

Another significant turnaround occurred in aviation kerosene. Until 2018, Brazil imported nearly all the jet fuel it consumed, with a deficit of USD 1.6 billion in 2013. From 2019 onward, the country began exporting more than it imported, and in 2025 exports reached USD 2 billion against imports of USD 930 million, generating a positive balance of USD 1.1 billion.

In the opposite direction, diesel remains the major bottleneck. Brazil imports more than 20% of all the diesel it consumes, and in 2025 external purchases totaled USD 9.5 billion, a record volume of 14.4 million tonnes. Over ten years, diesel imports nearly tripled in volume, rising from 5.9 million tonnes in 2015 to 14.4 million tonnes in 2025. Gasoline posted a smaller deficit, with imports of USD 1.6 billion versus exports of USD 590 million, but the imported share also increased, corresponding to about 10% of domestic consumption.

In the combined chapter of oil, oil products, gas, and coal, Brazilian exports totaled USD 55.9 billion in 2025, while imports reached USD 30.5 billion, generating a surplus of USD 25.4 billion. Ten years earlier, the country recorded a deficit of USD 12.8 billion in this same chapter. The shift to surplus occurred in 2018 for the first time, with a positive balance of USD 1.7 billion, and the result has improved every year since.

Oil’s share of Brazil’s total exports rose from 5.9% in 2005 to 16% in 2025.

Crude oil alone generated a positive balance of USD 37.9 billion for Brazil, while fuel oil added another USD 6.9 billion. On the negative side, diesel drained USD 9.1 billion, natural gas USD 2.6 billion, petrochemical naphthas USD 2 billion, coal USD 2.2 billion, and gasoline USD 1 billion. The country exports raw materials and imports finished products.

The foundation of this production is the pre-salt layer, which accounted for nearly 80% of total output in 2025, concentrated in the Santos and Campos basins along Brazil’s southeastern coast. Petrobras operated about 90% of national production, with destaque for the Tupi, Búzios, and Mero fields, drilled at depths between five and seven thousand meters.

The state of Rio de Janeiro concentrates 87.8% of all oil extracted in the country. Espírito Santo took second place in 2025 with 5.12%, surpassing São Paulo, which accounted for 4.89%.

Oil revenues already constitute a pillar of Brazilian public budgets. In 2024, royalties and special participation payments reached BRL 98 billion, distributed among the federal government, states, and municipalities, with Rio de Janeiro receiving the largest share.

Brazil’s proven oil reserves reached 16.8 billion barrels at the end of 2024, a 6% increase compared to the previous year. The reserve replacement ratio stood at 176%, meaning the country discovered almost twice as much as it produced during the period.

Brazil’s dependence on fossil fuels, however, goes beyond export revenues. Road transport accounts for 65% of freight transportation and 95% of passenger transport, according to the National Transport Confederation (CNT), pushing diesel and gasoline consumption to levels that the refining park cannot fully supply. Thermal power plants, activated during droughts, also burn oil products and gas, reinforcing the link between energy supply and fossil fuels.

In the early years of the pre-salt, the government planned to build new refineries to eliminate the deficit in oil products and turn Brazil into an exporter of industrialized fuels. Operation Lava Jato halted this plan: construction of the Rio de Janeiro Petrochemical Complex (Comperj) in Itaboraí was suspended in 2015, and the second module of the Abreu e Lima Refinery in Pernambuco was left unfinished. The main cost of suspending or canceling new refineries can be measured in the tens of billions of dollars spent on diesel imports that could already have been produced domestically.

The Lula administration resumed both projects. In March 2025, Abreu e Lima completed modernization of its first module, raising capacity from 115,000 to 130,000 barrels per day, and Petrobras signed contracts worth more than BRL 8.3 billion to build the second module, scheduled to start operating by 2029, when the refinery will double its capacity and become the company’s second largest. The former Comperj, renamed the Boaventura Energy Complex, inaugurated in 2024 the largest natural gas processing unit in the country and received BRL 13 billion in investments to build diesel, aviation kerosene, and lubricants production units integrated with the Duque de Caxias Refinery.

While new units are not yet ready, Petrobras has invested in expanding and modernizing existing refineries, raising utilization rates above 90% throughout most of 2025. Even so, installed capacity does not keep pace with demand growth, and Brazil’s Ten-Year Energy Plan estimates that the country will continue importing oil products over the next decade.

Reducing this vulnerability requires long-term investments in electrified railways, solar energy, nuclear energy, and small hydropower plants, as well as the progressive electrification of the vehicle fleet. These are paths that could, over the coming decades, reduce Brazil’s exposure to oil market fluctuations.

International oil trade totaled approximately USD 2.7 trillion in 2024, distributed among crude oil (USD 1.31 trillion), refined products (USD 890 billion), and gases, including liquefied natural gas and LPG. The ten largest exporters accounted for more than 83% of total traded value.

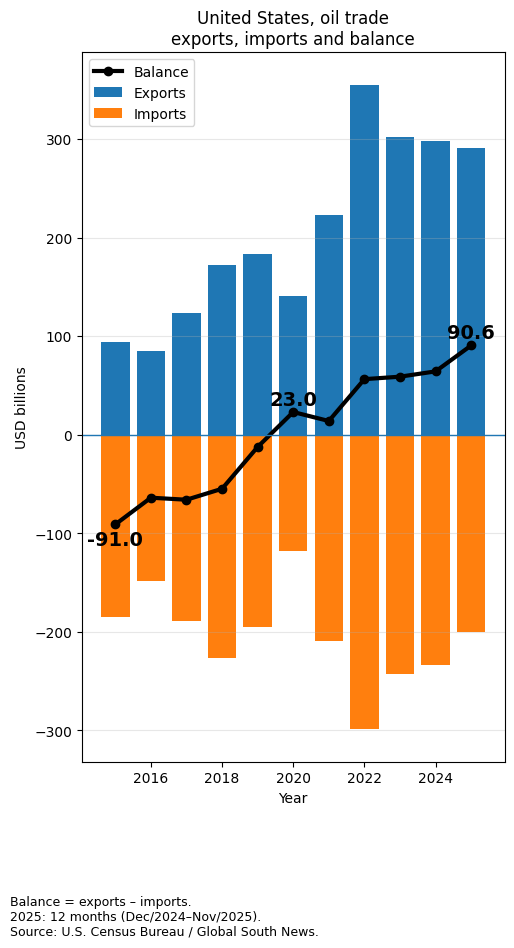

The most notable transformation in the oil market over the past two decades occurred in the United States. In 2005, U.S. oil imports peaked, and the country’s oil deficit reached USD 452 billion in 2008. The shale oil revolution reversed this equation: in 2020, the U.S. economy became a net oil exporter for the first time in decades.

In the twelve months ending in November 2025, U.S. exports of crude oil, oil products, and gases totaled approximately USD 291 billion. Of this amount, about USD 101 billion corresponded to crude oil, USD 110 billion to refined products, and USD 80 billion to gases. These figures place the country not only as a major crude exporter, but also as one of the world’s largest suppliers of finished fuels, alongside India, the Netherlands, Singapore, and South Korea.

In the same period, the U.S. oil sector posted a surplus of USD 90.6 billion. The leadership of these countries in refining and oil-product exports does not stem from large reserves, but from the scale and efficiency of their industrial parks.

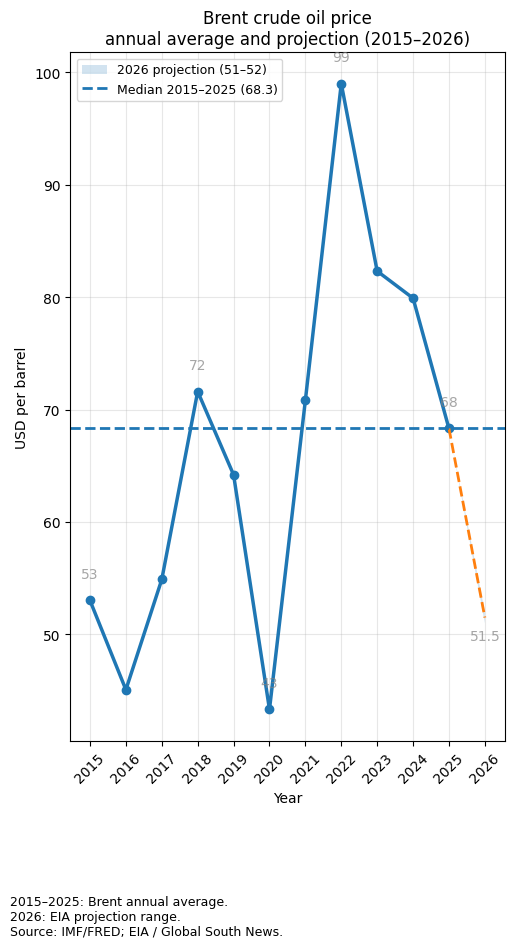

Oil supply exceeded demand by a wide margin in 2025, and Brent crude fell from an average of USD 80.5 per barrel in 2024 to USD 65. The most recent EIA projections point to a range of USD 51 to 52 per barrel in 2026.

The war in Ukraine reshaped flows between Russia and Europe. Europe purchased more than 54% of its oil and gas from Russia in 2015. By 2024, this share had fallen to less than 10%, while U.S. suppliers jumped from 6% to more than 42% of European imports.

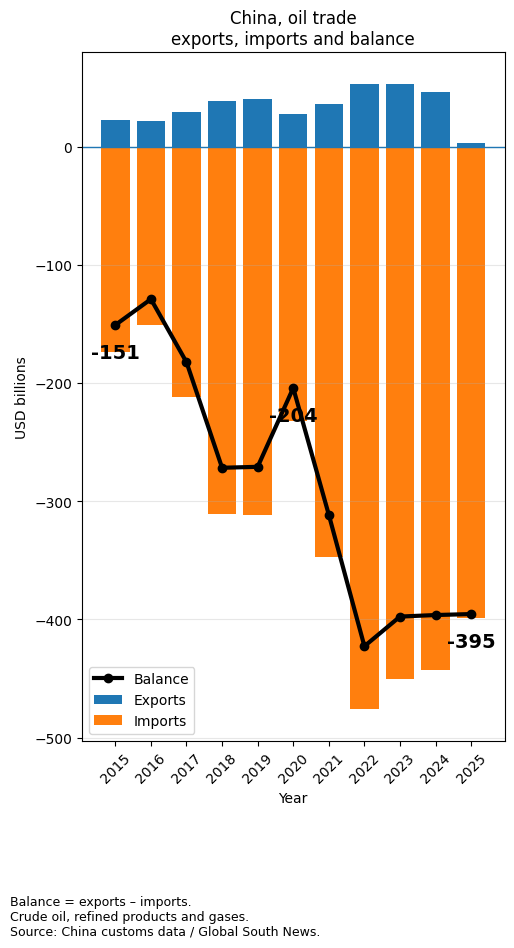

China consolidated its position as the world’s largest net oil importer, with a deficit of USD 395 billion in 2025 and a supplier list led by Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Brazil. Chinese demand for oil remains one of the forces sustaining global demand, even amid excess supply.

Global demand for oil products is changing in composition. By 2030, the International Energy Agency projects that petrochemical feedstocks will account for most consumption growth, displacing gasoline and diesel from the center of demand in favor of plastics, fertilizers, synthetic fabrics, and aviation kerosene.

Venezuela holds 303 billion barrels of proven reserves, Saudi Arabia 267 billion, Iran 208 billion, Canada 163 billion, and Russia 107 billion, according to OPEC. Brazil, with 16.8 billion barrels, occupies an intermediate position in this ranking.

The Equatorial Margin, which stretches across 360,000 square kilometers between Amapá and Rio Grande do Norte, has an estimated potential of up to 30 billion barrels, according to ANP. If confirmed, this volume would nearly triple the country’s proven reserves.

Petrobras began drilling an exploratory well in deep waters off Amapá in October 2025, after five years awaiting environmental licensing from Ibama. The company’s business plan foresees USD 3 billion in investments in the region over the next five years, with the drilling of 15 new wells.

The geological formation of the Equatorial Margin is similar to that of Guyana’s coast, where major discoveries transformed the small country’s economy, which has been growing at annual rates of 14%, according to the IMF. If estimates are confirmed, Brazil could become one of the world’s five largest holders of proven oil reserves in the next decade, combining pre-salt and Equatorial Margin.