I was in Caracas in the last week of July to participate in the “Voices of a New World” event, organized by the Venezuelan government. Communicators from across the Global South were invited, including representatives from Africa, Latin America, Russia, the Middle East, and China.

The experience provided me with encounters with press colleagues from different continents. I met the Iranian journalist Sahar Imami, who became internationally famous for continuing to host her show on IRINN (Islamic Republic of Iran News Network) even during an Israeli attack on the network’s studio complex in Tehran on June 16, 2025. Even after the explosion that left the studio in darkness and part of the building in rubble, Imami returned on air to conclude the broadcast.

Também encontrei o jornalista iraquiano Muntadhar al‑Zaidi, famoso por atirar seus sapatos em George W. Bush durante uma conferência de imprensa em Bagdá, em 14 de dezembro de 2008, proclamando: “Este é um beijo de despedida do povo iraquiano, seu cachorro”. Ele foi preso e, inicialmente, condenado a três anos, mas acabou cumprindo cerca de nove meses de prisão.

I also met the Iraqi journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi, famous for throwing his shoes at George W. Bush during a press conference in Baghdad on December 14, 2008, and shouting, “This is a farewell kiss from the Iraqi people, you dog.” He was arrested and initially sentenced to three years but ended up serving about nine months in prison.

However, the trip was especially valuable for another reason. This wasn’t my first time in Venezuela. I had been here in June 2015, when I accompanied a group of Brazilians organized by social movements to counter the narrative of senators who were trying to visit Leopoldo López in prison. On that occasion, however, I didn’t have enough time to truly get to know the country and its capital, or to interact with the local population. I found a country in a darker period then, with political instability still reverberating from the 2014 “guarimbas.”

This time, I was able to dedicate time to exploring the streets of Caracas alone, frequenting restaurants and supermarkets, analyzing prices, visiting malls and cafes, talking to locals, and observing life in public squares. I found a much calmer capital, a reflection of a more stable political moment in the country.

I discovered a beautiful, tidy, and safe metropolis, despite the traffic jams (typical of any large city), with an intense economic life. I didn’t see signs of poverty in the streets, people going hungry, or beggars. What I did see were well-maintained buildings, manicured squares, well-paved streets, and new cars circulating.

The public transportation system works very well. The Caracas metro is clean, organized, and extremely cheap—a ticket costs just 15 bolívares (about US0.23orR1.24). To put that difference into perspective: in Rio de Janeiro, the fare is R7.90,andinSa~oPaulo,it′sR5.20, making the Rio fare more than six times more expensive and the São Paulo one four times higher than the Venezuelan one.

Similarly, other basic costs are surprisingly different. Gasoline costs just US0.50perliter(aboutR2.70), which is less than half the average Brazilian price, which hovers between R5.60andR6.20 per liter. On the other hand, a large pizza with soda, costing US12(aboutR65), is more in line with Brazilian prices, comparable to what you’d pay at traditional pizzerias in capitals like Rio and São Paulo.

While trying to exchange money at a lottery office, I met an elderly Uruguayan man (who has lived in Caracas for about 20 or 30 years) who got emotional upon learning I was Brazilian. He had visited Brazil decades ago during Carnival and had fond memories of the country. I discovered that he used to be a journalist and had written a famous article titled “I Don’t Vote for Chávez”—a sophisticated rhetorical piece where he explained that he would vote for the social missions, the infrastructure programs, and everything Chávez had done to transform Venezuela, and not just for the president’s personal figure.

I spent hours reading at Bicicafé Descapada, in Plaza de la Juventud, Avenida Bolívar, near the National Art Gallery. The establishment, which is full of bicycles, also rents bikes and promotes tours around Caracas. There I saw young people recording TikTok videos, playing sports, rollerblading, cycling, and skateboarding in this important square in downtown Caracas.

🎥 Clique aqui para assistir ao vídeo da Praça da Juventude em Caracas

A striking characteristic is how Venezuela maintains policies from the Chávez era that truly work. Fuel is extremely cheap—I even photographed the prices to prove it. This policy, along with affordable public transportation, facilitates urban mobility and reduces the cost of living.

I had the opportunity to meet Bruno Falci, my Brazilian friend who works at Telesur (and is also a correspondent here at Cafezinho), accompanied by his friend Yoleny Useche, communications manager and head of press for the Agitation, Propaganda, and Communication area of the PSUV..

During a walk back to the hotel one night, I had the only negative incident of the trip. An unbalanced person attacked me on a deserted street, but I managed to defend myself and get out of the situation unharmed. The episode served as a reminder that in Caracas, no matter how safe it may be, as in any big city in the world, you have to be careful when walking at night.

At the Caracas airport, I tried some delicious arepas that I’ll miss. The airport is functional and clean, although it deserves a larger structure considering the city’s size and population.

The Venezuela I encountered directly contradicts the predominant narrative in Brazilian and international media. It is not the country in collapse that is so often portrayed. There are problems, certainly, as in any nation, but there is also normal life: people working, studying, and having fun, a functioning economy, and active commerce.

The American sanctions caused real damage, but the country has adapted and found solutions. In a way, there has been a more efficient currency accommodation. The government is demonstrating pragmatism, far from the image of an inflexible dictatorship that is often spread.

Caracas surprised me in a positive way. It’s a vibrant city that, like all of Venezuela, has managed to find a place in the world to develop, to sell and buy products, and to expand its possibilities. It’s worth visiting to form your own opinion based on direct experience, not on preconceived narratives.

My experience left me even more convinced that Brazil should advocate for Venezuela’s entry into the BRICS, because it will be an important space for the country to defend itself from imperialist attacks by the United States.

Urban art in Caracas

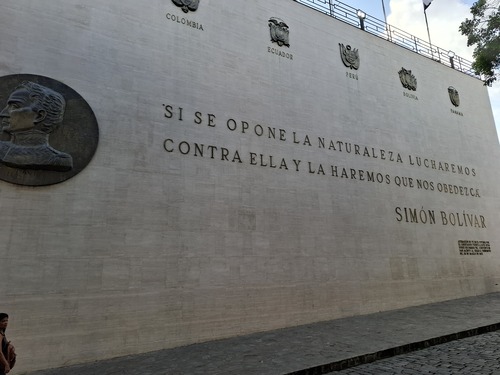

National symbols and Bolívar

Other images of Caracas

🎥 Click here to watch the video of the dancing in Bolívar Square.

In Plaza Bolívar, in the historic center of Caracas, next to the house where Simón Bolívar was born, I saw locals participating in a kind of free dance class.