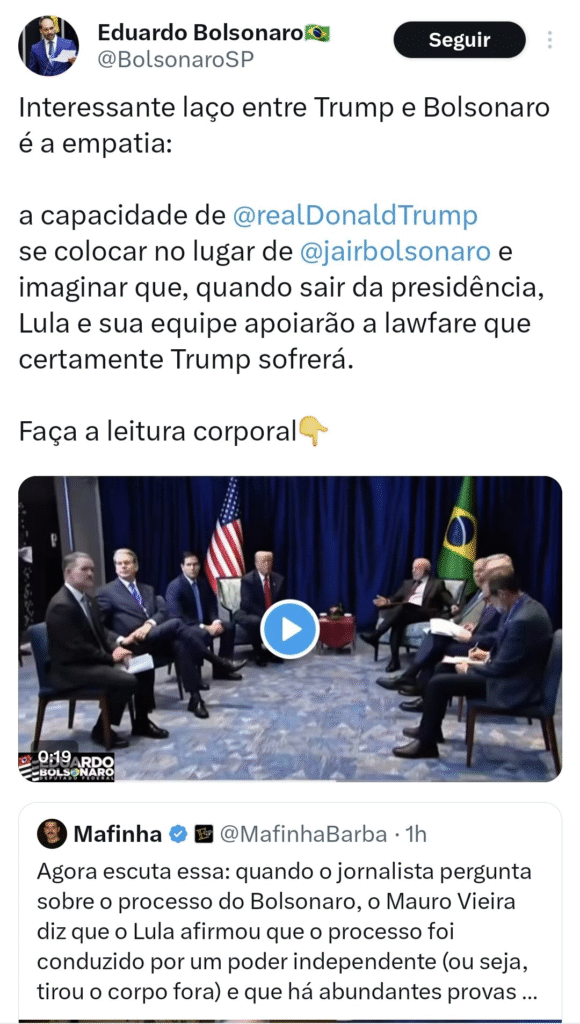

It is ironic that our nation’s arch-traitor, federal deputy Eduardo Bolsonaro, son of former president Jair Bolsonaro, self-exiled in the United States and articulating sanctions against Brazil, has resorted to “body language” to try to disqualify the meeting between Lula and Trump, which took place in Malaysia today, October 26, 2025.

“Bananinha” [Little Banana], completely devoid of arguments, resorted to an esoteric issue that only he saw.

But “body language” and other symbols are, in fact, relevant. The images clearly showed Lula completely dominating the meeting.

First, notice that he occupied the position to the right of the video. This is a determining detail, as the human eye looks first to the right, and Trump usually sits on the right in the Oval Office to humiliate heads of state. This time, it was Lula who took that position, as if he were chairing the event.

Furthermore, the distance between them, as a symbology of power, has always been central. And Lula’s body language denoted a relaxation and control that contrasted with Trump’s posture.

While Lula remained reclined, with his legs crossed and a calm expression, Trump leaned forward, tense and on the edge of his chair. Lula adopted the position as if he were the owner of the house. This is, without a doubt, significant.

Finally, it was Lula himself who set the rhythm of the event, disarming the last trap of the preliminary press briefing. The journalist from Globo started to ask Trump about Bolsonaro, and Lula delicately ended the briefing, suggesting it be done after the meeting. Trump agreed, even joking that the questions were boring.

This symbolic victory reflects something deeper: the consolidation of Brazil’s material power in the world, sustained by its productive base. Among the reasons for Brazil’s geopolitical power is the strategic importance of agribusiness. And on this, the progressive camp and intellectuals specialized in development must also update themselves.

Brazilian agribusiness, today, is a sector of relative complexity. It would be frivolous to call it a low-elaboration activity. It is, in fact, a sector of growing sophistication due to the need to compete internationally, to offer high performance, to preserve the environment, and to maintain yield.

You have to know the chemical composition of the land, know how to deal with irrigation, with the weather, with the market. All of this is a difficult activity. The issue of stocks, the time you can wait so the product doesn’t perish, all of this requires knowledge and technology.

And, above all, with the very large increase in the world population and the specialization of the global economy, the technological issue is fundamental, but without food, there is no life. The world can even live with a shortage of chips, but without food, everyone dies. It is much more comfortable for countries to have a guarantee of food security, of supply from Brazil, so they can dedicate themselves to other things.

In the case of China, with its 1.4 billion inhabitants, and Indonesia, with over 280 million people, this is very clear. Populous countries in Asia and Africa need food. China is, today, totally integrated with Brazil in a way that we could call existential.

Brazil guarantees the survival, the food security of China, and not just China, but of Asia and the whole world. We are not talking about just any food. These are strategic products for the basic nutrition of the human species. Brazil guarantees global protein. Soy is an eminently protein-based vegetable product.

So Brazil is the great exporter of meat and soy. In addition to other products, like cellulose, which is part of the global infrastructure, and iron ore, which is the productive structure. Brazil also exports, nowadays, large quantities of oil.

Brazil stands out as a major oil exporter because its internal energy matrix is relatively clean, which allows the extracted oil to be exported in large volumes, without the need for massive internal consumption.

By combining clean energy, food abundance, and institutional stability, Brazil consolidates itself as an indispensable power in the world order.

Notes for International Readers:

- Eduardo Bolsonaro: The son of former president Jair Bolsonaro, a federal deputy, and a key figure in the “Bolsonarist” movement, strongly aligned with right-wing international figures.

- “Bananinha” (Little Banana): A common pejorative nickname used by the Brazilian left for Eduardo Bolsonaro.

- Globo (Rede Globo): Brazil’s largest and most influential media conglomerate, often seen as a powerful political player.

- Progressive camp (campo progressista): A general term for the Brazilian left and center-left political sphere. The author is arguing that this camp must “update itself” and recognize the technological sophistication and geopolitical importance of Brazilian agribusiness, a sector often criticized by the left for environmental and social reasons.