We are delighted to introduce our newest columnist, Priscila Miranda. A specialist in cinema and the audiovisual arts, she will be sharing her sharp insights and analysis with the readers of Global South News.

Priscila is also the director of Phoenix Filmes, a film distribution company known for its curated selection of movies and its operations in Brazil, France, and other parts of the world. Her industry experience brings a unique perspective to our team.

Her columns will be published regularly here at Global South News. For our Portuguese-speaking audience, you can also find her work at Cafezinho. We invite everyone to follow her upcoming contributions.

The Chinese dream, Resurrection, the Fiat Lux film of the year!

By Priscila Miranda, for Global South News and Cafezinho

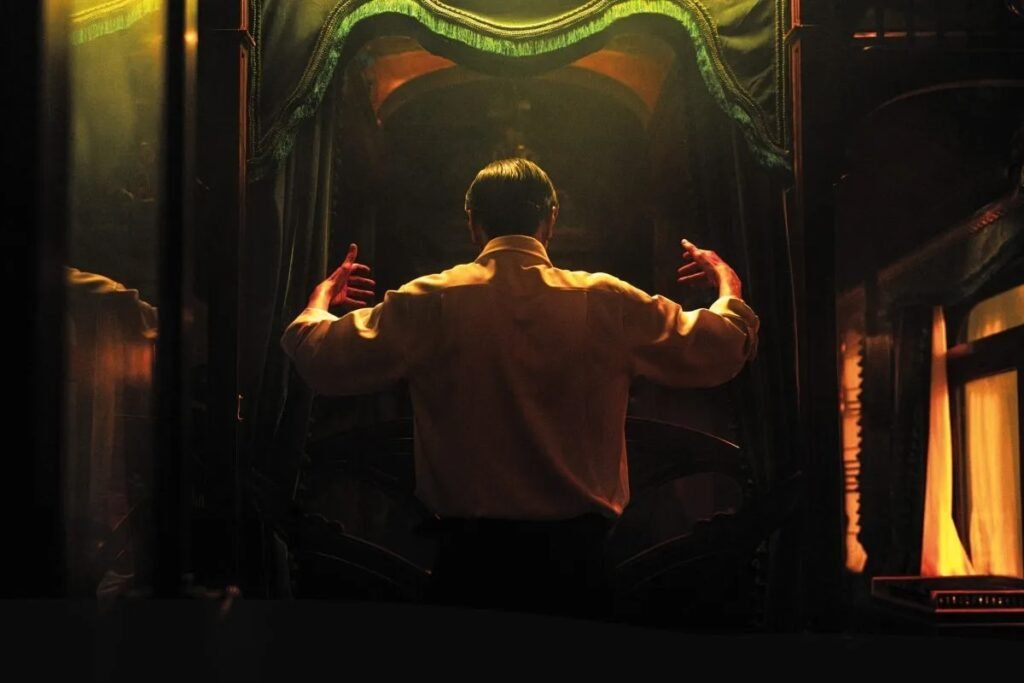

If there is a film that represents China in contemporary cinema, that film is Resurrection, by Bi Gan.

Not only because of its formal ambition or its technical scale, but because it asserts something much deeper.

China’s definitive entry into the realm of imagination, into the terrain of soft power, into the space where countries cease merely to exist and begin to be dreamed.

In its opening weekend, Resurrection debuted at number one at the Chinese box office, grossing RMB 116.8 million (around US$16.5 million), according to The Hollywood Reporter. Since then, the film has surpassed US$25 million in box office revenue exclusively in China—an absolutely exceptional performance for a work of art of such formal radicalism and aesthetic ambition.

Resurrection premiered in the Official Competition at the Cannes Film Festival, the world’s foremost showcase for cinema. This is no coincidence. For decades, Cannes has set the tone for international film circulation and has directly influenced the most important film award, the Oscars. Year after year, the titles that consolidate themselves during awards season receive their first symbolic legitimation there.

In this same circuit are films such as Sentimental Value, by Joachim Trier, The Secret Agent, by Kleber Mendonça Filho, and Sirât, by Oliver Laxe. Resurrection belongs to this group. It did not merely pass through Cannes—it divided Cannes, as great works do.

Bi Gan is 36 years old. Resurrection is only the third feature film of his career—and yet it is a work that few countries in the world would be capable of producing. It is art cinema on an industrial scale, something today restricted to very few systems of film financing.

This is not about stating a fixed budget figure—it is about recognizing magnitude. The production time, technical complexity, aesthetic ambition, and the level of risk involved place Resurrection in a category comparable only to the great auteur works produced by cinematographies with enormous economic muscle.

Today, only China—and historically the United States—are able to sustain this type of cinema: poetic, radical, experimental cinema, made with cutting-edge technology, national stars, and an international vocation.

Who would make a film like this?

Perhaps a Scorsese would have the structure.

But he would not make it like Bi Gan.

Because only an artist formed within contemporary China—a country that has already won its material battles—could make a film that speaks of dreams, memory, time, and the very essence of cinema.

Resurrection is, above all, a tribute to cinema.

It is not a didactic film, nor explanatory, nor concerned with representing a society in a literal way. Art does not exist to freeze a country in a fixed portrait. Society is in constant mutation. Art is poetry, displacement, invention.

What Bi Gan does is assert something far more powerful: mastery of cinematic language in its essence.

A film is a painting in motion.

It is 24 frames per second.

It is technology, coordination, time, money, and risk.

And once again, this is only possible because China today has the means to make it happen.

After Cannes, Resurrection was acquired and distributed internationally. The film has distribution in the United States, has just been released in France, and continues to circulate within the prestige circuit.

Actress Isabelle Huppert stated that she had not seen a film of such cinematic grandeur in years.

IndieWire included Resurrection on its list of the 50 best films of the year, at number 23—recognition that places the film at the center of international critical debate.

In Italy, Resurrection is distributed by I Wonder Pictures, led by Andrea Romero.

Andrea Romero is today one of the boldest and most visionary distributors in contemporary Italian cinema. And here, boldness does not mean reckless betting or trend-chasing. It means historical recognition.

Over the past few years, Romero has been one of the professionals best able to identify films that matter to the history of cinema. Films that pass through Cannes, that reach the Oscars, but above all films that endure—films that continue to be seen, debated, revisited.

That is why, when Resurrection is endorsed by him, it is not a fleeting enthusiasm. It is also a historical seal: recognition, by someone who reads cinema in the long arc of time, that this is a film that enters history.

Bi Gan is the product of a new generation of successful Chinese citizens.

And this is decisive.

Truly wealthy countries are not those that produce only doctors, engineers, or lawyers. That is the foundation. That is structure. Truly fulfilled countries are those capable of producing artists.

It is no coincidence that elites throughout history have always invested in art, culture, and patronage. Because real power lies not only in material production, but in the capacity to imagine the world.

Bi Gan emerges from this place.

From a country that has already conquered the material and now competes in the immaterial.

From a country that understands that the next step is not to convince, but to enchant.

Resurrection is a Fiat Lux film.

Let there be light.

It does not explain China.

It creates a world.

It does not dispute the past.

It disputes the dream.

And in the end, we humans are far more dream than reality. Public policies, state projects—all of this should be in the service of that dimension, the one that makes us infinite.

That is why Resurrection is not only the great Chinese film of recent years.

It is a film that enters the history of cinema.

And it enters because it affirms, with aesthetic force and artistic courage, that a Global South country can produce not only infrastructure and technology, but art.

This is power.

This is cinema.

Resurrection will be released later this year in theaters across Brazil by distributor Fênix Filmes.